A Day in Arcadia: CHARLES COCKERELL

The British Museum, keeper of the ‘Elgin marbles’ has another sensational frieze, removed from the Temple of Apollo Epikourios in Arcadia, Greece by English Grand Tourist Charles Cockerell.

While shouty newspaper ‘letters to the editor’ and raised voices on social media argue for and against the return/retention of the Parthenon marbles - taken from Greece under Turkish occupation - inside the British Museum is an ancient Greek treasure that rarely gets a mention. It usually needs a BM warden to remove the red rope barrier to let visitors see it. Would that be 5th-century BC Greek vases? Would it be Greek statuary? Would it be a marble caryatid? None of those. It is a rare frieze removed from the 5th-century BC Temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassae (modern-day Vasses), near Phigalia (Figalia) in Arcadia, by English architect Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863), on his Grand Tour of Italy, Greece and Turkey from 1809-17. This happened when Greece was under Turkish control.

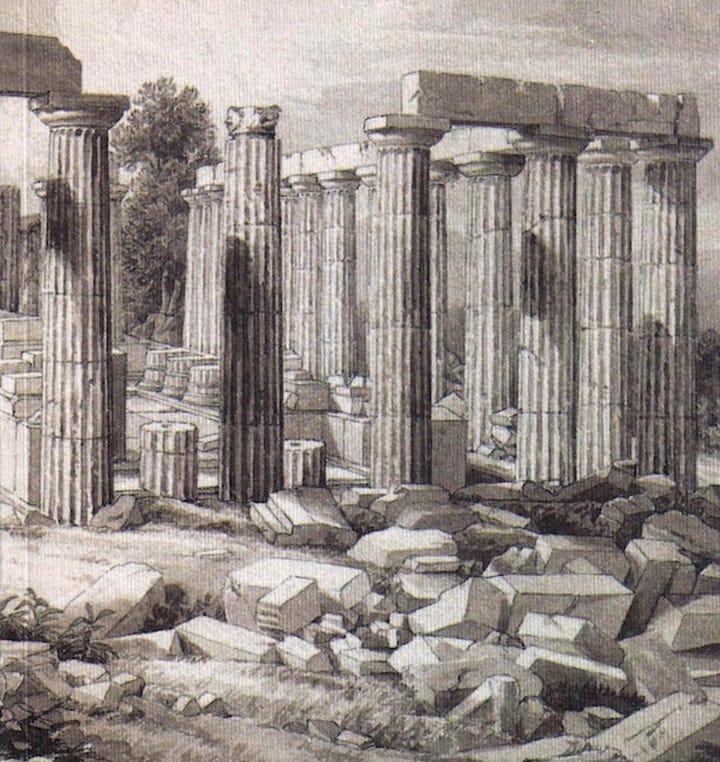

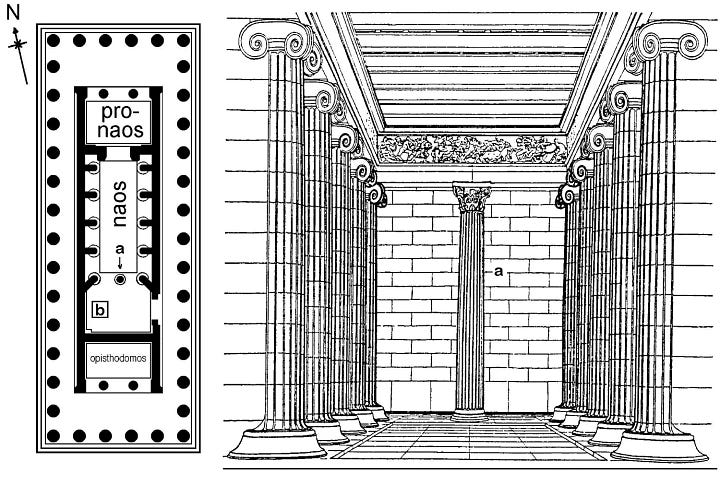

Why is the temple unique? For a start, so many of its attributes are one-off rarities including its size, direction, and the columns – the only temple of this era to use three column orders. Doric on the exterior, Ionic for the interior, and a single Corinthian column, plus its remarkable frieze. The temple is long and thin, 128 x 48 ft (39 x 14.6 m) and built c.429-400 BC on the ridge of a wooded glen, (bassae=little vale in the rocks) on the slopes of Mt Kotylion. It was built on a north-south alignment, not the usual east-west. An ironwork grille door was probably created in the east wall to allow light to enter and shine on the statue of the god Apollo, and visitors to view it without entering the temple. The exterior has six Doric columns by fifteen. It was said to be designed by Ictinus the architect of the Parthenon associated with the Classical period in ancient Greece but the temple is Archaic – older period - in design. It was built of local limestone.

The thinking here is that building work started and was interrupted by the Peloponnesian war (431-401 BC) between Athens and Sparta, so it had a later completion date. It is 3700ft (1131 m) above sea-level and until 1959 inaccessible by road. Visiting it in the heat of summer, the temperature is pretty cold by the time visitors reach 1131 metres up on a mountain top. And since 1987 the temple has been covered with a white protective nylon tent to preserve it from acid-rain. This is a remote area. One can imagine ancient Greek gods hanging about here bathed in low cloud, bellowing out a few thunderclaps to worry the local population.

In 1811, Cockerell alongside Baron Haller von Hallerstein, an artist, and others travelled to Arcadia to find the temple, record its measurements and make drawings. 36 of its 38 columns were still standing. He was not the first to travel through a challenging terrain to the temple site. The first to rediscover it was a French architect Joachim Bocher in 1765. He returned in 1770 for further research and was killed near to the temple by bandits, reportedly for his brass buttons that were thought to be gold.

Why such interest in this temple? The key is an ancient Greek travel writer, Pausanias (1-2nd century AD). He was born in an era when Greece was controlled by Rome. He wrote a travel-history book Description of Greece and describes the temple in his section on Arcadia, mentioning its date, the architect, the architecture and the name it was given ‘Apollo the Helper’. He is the only ancient writer to mention this temple, perhaps due to its remote location. He did write that Ictinus the architect of this temple also built the Parthenon. Annoyingly for historians Pausanias failed to mention the Bassae frieze. He didn’t enter the temple so could not comment on the unique Corinthian column or the interior frieze. It is not possible to know if these were in place in 1-2nd century AD.

But what about the frieze? Why the rarity? It was not in place when Cockerell visited but two pieces were found, he recalled ‘ In looking about I found two very beautiful bas-reliefs under some stones’. The group searched and found more pieces buried under grass and earth and stones. A fox’s underground lair revealed more pieces. Later, looking at the wall structures that were still standing, it was clear that the frieze was placed on the interior walls, not exterior as the Parthenon frieze was. There is no other temple in Greece that has a frieze on the interior. And when it was finally all found, the high-relief figures were in 23 panels, measuring 102 x 2 ft (31 metres & 63 cm).

The remains of a building discovered to the north of the temple with a room of the exact proportions of the frieze with marble and metal shavings, might be the location of its creation. Examination of the figures revealed the hands of three sculptors at work. The frieze narrative relates to the mythic battles between Greeks and Amazons, and Lapiths and Centaurs. It is a remarkable record of ancient Greek myths. The fight scenes are sensational, the Amazons – female warriors – fighting hard with gruesome killings. This could symbolise Arcadians who were acclaimed for their strength and toughness.

Cockerell and a larger group returned with a permit from the Turkish government to visit the site and in 1813 with a permit to excavate. By arrangement with Ali Pasha, a Turkish government representative, half the proceeds – money made – would go to Ali Pasha. No Greek had a say in what happened to the temple, its marble frieze and statuary. Perhaps the Greek government does not shout for it now because the temple is not in a state to have the frieze put in place and there is no museum to house it on the mountain-top. If you – like me - are interested in the history of ancient Greece and its temples, Pausanias’ Descriptions of Greece is the book to read. And Room 16 at the British Museum (make sure you get taken up the short flight of stairs to see the frieze). Even better, visit the western Peloponnese, to find Arcadia – the land of milk and honey – to reach the Temple of Apollo Epicurious at Bassae. It’s truly memorable, especially when drum rolls of deep thunder shake the ground you are standing on.

Text copyright Rosalind Ormiston 6 December 2023

Images: copyright Raddato, C. (2016, July 06). Temple of Apollo, Bassae. World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/image/5291/temple-of-apollo-bassae/